The Maltese Falcon

Set in San Francisco, The Maltese Falcon introduces the audience to Sam Spade, a private detective who works with his partner, Miles Archer. When a prospective client named Ruth Wonderly enters their office, she hires Archer to find a man named Thursby, who she claims has kidnapped her sister. After bidding his partner farewell, Spade is later shocked to learn that both Miles and Thursby have been murdered. The police suspect that Thursby killed the investigator and imply that, in an act of retaliation, it was Sam himself who shot Thursby.

After she tells him her story was fake, he's approached by a man going under the name Cairo, who hires him to retrieve a statue of a bird, the Maltese Falcon. Now understanding that everything that has taken place was in pursuit of the bird, Spade does his best to search for it. When he tracks down a ship at the docks, it isn't long before he finds the bird in the arms of the vessel's murdered captain.

Having hidden the bird, Sam learns that everything traces back to a business mogul and smuggler named Gutman, whose hired goon had trailed him before. Meeting at the hotel, he tries to strike a deal to turn someone over for the murder of Thursby, still hiding from the audience who killed Archer. After convincing Gutman and Cairo that they're safe to leave, he has the police pick them up. In a twist for the ages, he then reveals that it was Brigid who murdered Archer, hoping she could pin the crime on Thursby, not expecting his own murder.

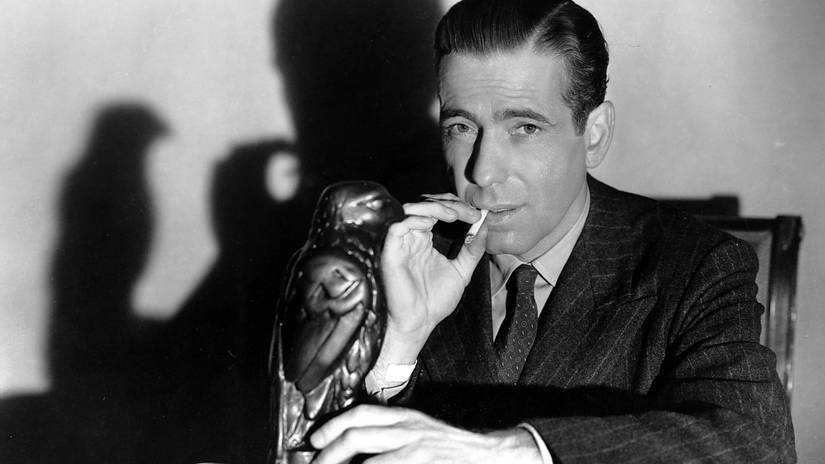

Everything about the film defined what the American Noir movement was made of, from the attitude of Humphrey Bogart, the constant deception, and Mary Astor embodying the ultimate femme fatale. The novel itself had a similar effect, basically creating the hardboiled detective genre when Hammett published it in 1929. Thanks to the success of the story, there was a place for the stories of authors like Raymond Chandler and Walter B. Gibson.

How Humphrey Bogart Made Dashiell Hammett Even More Iconic

The ending of The Maltese Falcon sees Sam Spade, fake falcon in hand, bitterly have to turn Brigid over to the police for the murder of Miles Archer. After watching the officers take her away, Spade hands the falcon over as evidence, prompting a detective to ask what it is.

In the final seconds of the film, the private eye simply responds it's "the stuff that dreams are made of," a line that came to define not just the story, but the Noir sub-genre itself. Over the years, countless films tried to find as perfect an ending as John Huston's masterpiece, but always came up short. The closest thing to a true contender was Roman Polanski's Chinatown, which fades to credits after the iconic "forget it, Jake, it's Chinatown."

Spade's reply adds a layer of tragedy to the already somber mystery movie. Knowing it to be a counterfeit, he can't help but look back on the murder of Archer and the loss of Brigid's innocence for having murdered a man, as all for nothing. All the trouble caused by her, Gutman, and his crew was in pursuit of something that was never even real. Above all else, the character is lamenting the effect that greed and the pursuit of broken dreams have on people, driving some to take a person's life. Likewise, he's considering his own loss of O'Shaughnessy, who, despite loving her, he had to turn over all because of what she did to try to get the falcon.

In the falcon, Sam sees an encapsulation of the worst of what people can do, and it might as well represent all the worst trappings of humanity. Upon learning of its false nature, even the audience can't help but feel deflated, looking back at all the grief it caused Sam and arriving at his conclusion: it wasn't worth it.

The Maltese Falcon is Still a Great Murder Mystery

Eighty-one years after the film's release, The Maltese Falcon is still an integral part of the murder mystery genre. A story gently influenced by the allure of adventure, it gave audiences the definitive hardboiled private eye, someone who influenced characters like Philip Marlowe and JJ Gittes. Unlike the conventional whodunit, these stories go out of their way to make solving the mystery virtually impossible until closer to the end. Like Sam Spade, the audience is supposed to feel lied to and out of their depth, only for the story to come into full focus in the final act.

Surprisingly, the film was actually Warner Bros' third adaptation of Hammett's story, the previous two having flopped as poor takes on the source material. In hindsight, the idea wouldn't have worked without Huston at the helm, nor Bogart's deep voice bringing Sam Spade to life as nobody had done before. Knowing how to end a movie is essential, and the '41 classic understood how to enhance the '29 novel just enough to make a great ending a masterpiece.